Facilitating Your Way across Everest

Ah, well-facilitated meetings. Despite (or perhaps because of) the plethora of meetings we must endure in our professional lives, few ever truly deserve that label.

Badly facilitated meetings are perhaps the greatest wasters of corporate time, a source of consistent frustration, and the bane of employees everywhere. Being asked to be a facilitator can feel akin to a request to be ritually sacrificed.

Nevertheless, when you ask people what they imagine under a ‘well-facilitated’ meeting and how to achieve it, few will be able to move beyond some clichéd descriptions. Ask what they consider to be bad facilitation though, and the resulting torrent of comments will make it seem like you’ve penetrated their deepest emotional reservoirs.

Thus the paradox of good facilitation: universally desired and exulted, yet very effete and hard to pin down.

During my time in student NGOs, project groups and at university, I spent thousands of hours in meetings of various kinds, and spent hundreds of hours facilitating meetings and events myself. As a result I feel like I’ve managed to break this hydra down into some clearly defined parts.

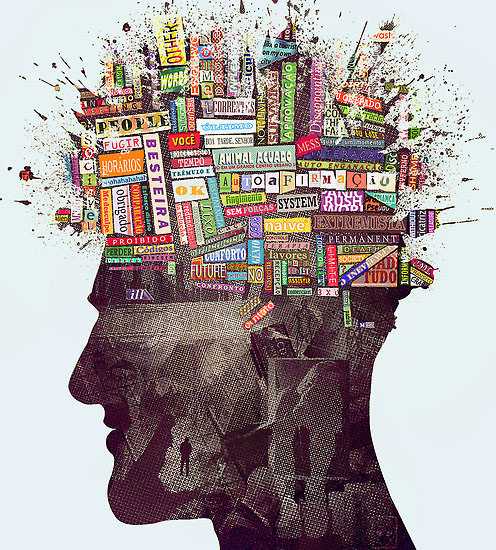

Let’s start with a broad perspective: facilitation is ultimately about reducing the time that goes into a discussion, while still making a high-quality decision that people feel ownership about. In this sense, the responsibilities of a facilitator are very broad, and not just restricted to avoiding the standard “time wasters” and keeping people from talking over each other.

The basics are important, sure, but a great facilitator must realise that any kind of talking takes time! Any sentence someone speaks in a discussion is either necessary or unnecessary, and one must plan to get as many of the former as possible and as few of the latter.

In other words, I submit that good facilitators eliminate time wasters and make people feel good about a meeting, but great facilitators proactively use methods to get people on the same page quicker and without losing anything of value.

Time wasters come in many forms.

Time wasters come in many forms.

In my mind, there are five questions that a facilitator should constantly ask him- or herself. In order of importance:

- Does this need to be discussed at all? And does it need to be done now?

The first step to making a discussion move faster is by cutting away the parts that aren’t actually required. The best way to do this is to have clearly defined the goals for the discussion, and ruthlessly (more or less) cut or redirect anything that doesn’t fall under that list.

Also take special care to cut things which are either irrelevant or not actionable; various forms of complaining and bitching frequently masquerade as productivity… - Do we have to discuss this with everyone?

Being in a bigger group makes things last way longer. In a group of 20 people it takes at least twice as long for everyone to state their opinion than in a group of 10. Ditto for getting on the same page. Further, the amount of interjections and clarifications increases geometrically.The main tools to avoid excessively large discussions are:

– Delegating a discussion to a smaller group (specialised team) or to another time (someone does research on it, comes back with a proposal; rather than everyone trying to analyse a basic situation)

– Making use of time more efficiently by splitting into smaller groups, which means that multiple people get to speak. This is where facilitation methods like world café, open space technology, group homeworks, etc. can be very useful. Huge time gains can be made with these methods, but keep in mind that there needs to be a convergence of the groups at the end, and this will take time as well. - Do we have to discuss it in this way?

Once we have established that this is a discussion worth having, and worth having with everyone, we can move on to wonder if any specific discussion method would make things more efficient. Here there is a very broad list of potential facilitation techniques, and it’s good to have a couple in your toolbox.Some of my personal favourites:

– Using silent clustering instead of group discussions/brainstorming. This is a subtle way of basically keeping people quiet, and using everyone’s brains at the same time! Through the silence, it will become clear that many things are either already agreed upon by the group, or need just a minimum of thought.

– Mindmapping. A complex discussion often needs on-the-spot visual tools, and a few minutes of mindmapping (or just writing down pros & cons) instantly improves clarity.

– Posing specific questions that refocus the discussion. “We unfortunately can’t change the past, so what can we do right now to improve this problem?” is a classic move that avoids excessive complaining and hindsight bias.So far, our considerations were quite high-level, and entirely focused on the process of the discussion itself. These final two are more granular:

- Can I help the discussion along?

At a more detailed level (of content): can you as a facilitator involve yourself in the content of the discussion to help out.Examples here would be:

– Work out misunderstandings between members who are moving in a circle

– Paraphrase things if they’re not clear

– Involving other people when one person is dominating discussion - Can I improve the atmosphere?

This is about the room, energy, eliminating distractions and noise, etc. Be aware of the right time to call a break, perform a wake-up activity, give participants some glucose, or clear out tension.Because it is so continuous, an argument could be made that it should actually be the first consideration. However, I find that there’s no point in improving the atmosphere of a discussion before you’ve determined that it’s actually necessary and that it’s happening in the least frustrating way. (But checking the atmosphere should definitely be part of preparation)

Oh and: don’t look down.

Oh and: don’t look down.

A final critical insight is that facilitation is primarily about trust, and this is why preparing for such a role should be taken exceptionally seriously. The very real (but unspoken) assumption is that the facilitator is like an experienced sherpa who will guide participants through a difficult discussion, avoiding the steepest hills of disagreement and the dullest valleys of boredom. He pays full attention to how the trip will go (process) while the participants trust him to guide them well, so they can focus on the view during the trip (content).

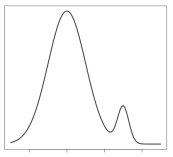

However, once participants start losing faith in the facilitator, all goes off the rails. Participants start thinking that maybe he or she isn’t quite up to the leadership task, and they start paying attention to the process as well. Soon they are offering their earnest suggestions to improve the process and begin to undermine the facilitator’s authority in subtle ways. As a result, less and less people are fully focused on the actual content, and we enter a downward spiral of mistrust, distraction, and progressively lower levels of discussion.

To avoid this, make sure you have prepared the path of discussion exceptionally well. This includes:

- Thinking through all of the points where problems might arise

- Question your assumptions about which parts of the meeting will go smoothly

- Be prepared for worst-case scenarios and failed discussion techniques; have at least a plan B and C ready.

Keep all these pointers in mind, and you too can become a reliable facilitation sherpa.

– Never thought I’d debate next to a Republican

– Never thought I’d debate next to a Republican

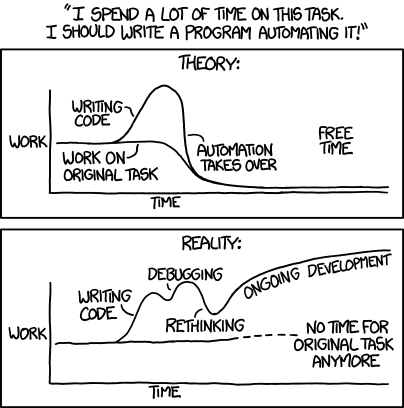

“Just teach ’em about value for time. Easy way to increase their hours”

“Just teach ’em about value for time. Easy way to increase their hours” Which is pretty illogical! Badum-tssschchkkchkkkkchkk *dropped my drumsticks*

Which is pretty illogical! Badum-tssschchkkchkkkkchkk *dropped my drumsticks*

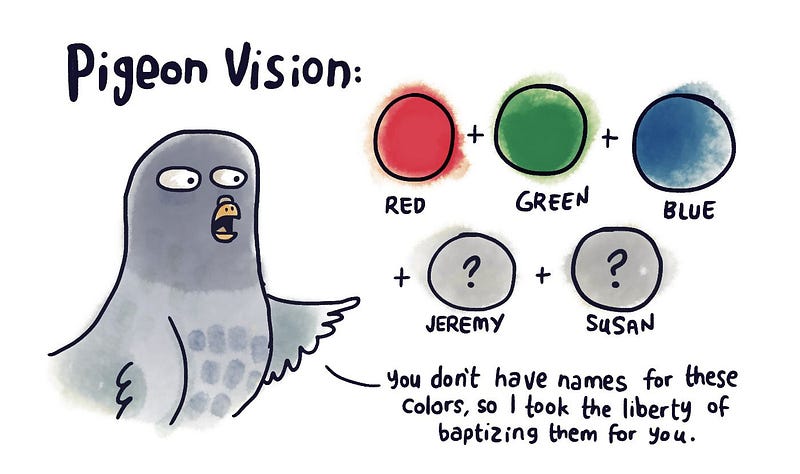

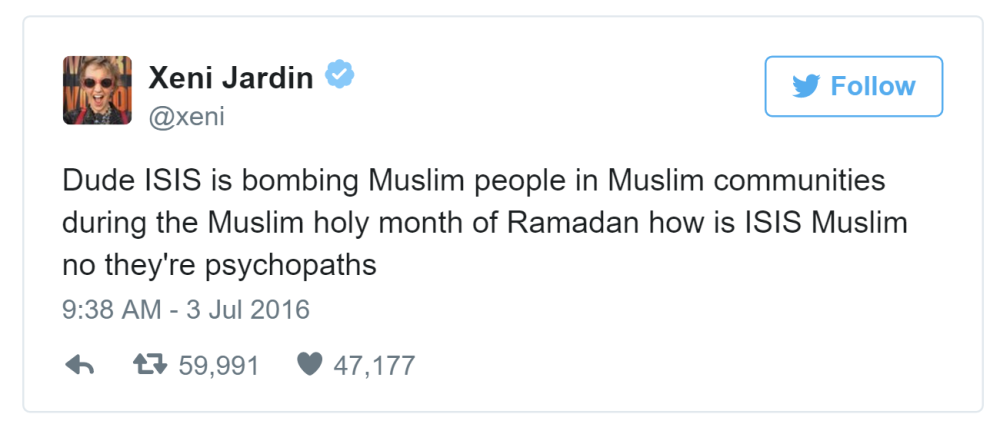

If real muslims never kill muslims; and terrorists kill muslims; then terrorists can’t be real muslims!

If real muslims never kill muslims; and terrorists kill muslims; then terrorists can’t be real muslims!

Or perhaps the truth must be locked in a meandering labyrinth few are destined to find?

Or perhaps the truth must be locked in a meandering labyrinth few are destined to find?

Look away, this is classified!

Look away, this is classified!

Never thought I’d research Oprah for my blog, but there you go.

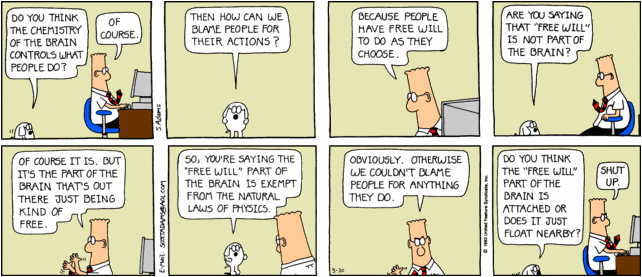

Never thought I’d research Oprah for my blog, but there you go. Hearing people defend free will is rather amusing though.

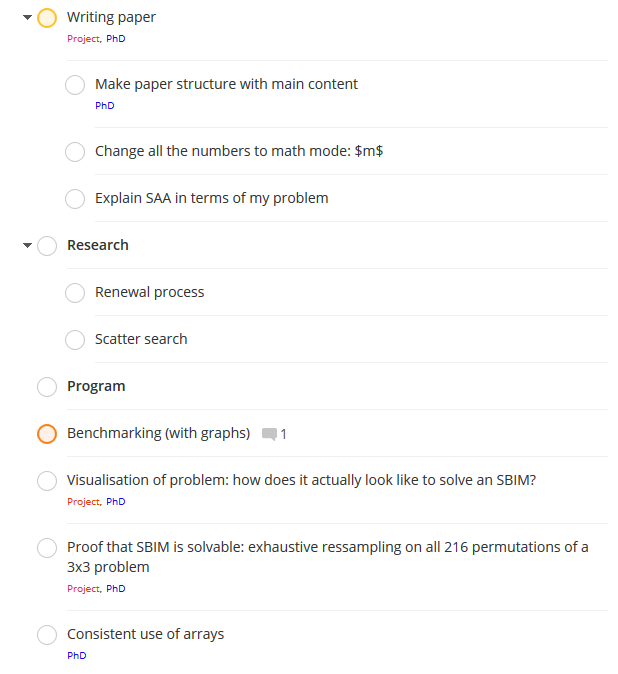

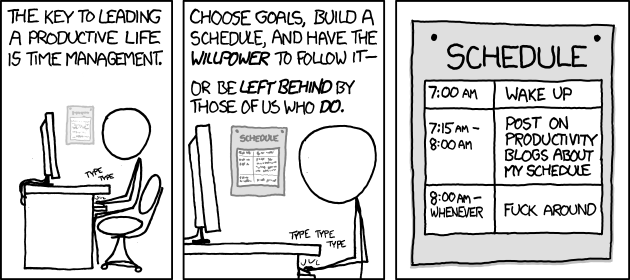

Hearing people defend free will is rather amusing though. My game plan for this Sunday.

My game plan for this Sunday. I also learned to avoid the dreaded “Varia” category.

I also learned to avoid the dreaded “Varia” category.